Being a song that was passed down orally, The First Noel may date to the 13th or 14th century. Some believe the song was inspired by a dramatization of the Christmas Story where actors would act out vignettes as they sang. The song does tell the story of Jesus’ birth from Matthew 2 and Luke 2, and would have worked well as a dramatized song with a repeating chorus.

The word “Noel” is French for “Christmas” which is derived from the Latin word “Natalis,” meaning “Birthday.” Even though “Noel” works well for the chorus of The First Noel, it’s strange to consider that when the ancient singers arrived at the chorus of each verse that they were simply singing, “Christmas, Christmas, Christmas, Christmas….”

The First Noel was first published by Davies Gilbert in 1823 in Some Ancient Christmas Carols. Ten years later, William Sandys published the song in Christmas Carols Ancient and Modern increased the popularity and prominence of the carol. The song originally had nine stanzas, but five are most commonly used today. In most recordings, artists rarely perform more than two or three verses which is a shame because it causes people to miss out on the story of the song. Though the angels appear to the shepherds in the first verse, most of the carol focuses on the journey of the wise men, giving the carol an Epiphany focus. The fourth verse is one of my favorites:

“This Star drew nigh to the Northwest; O’er Bethlehem it took it’s rest.

And there it did both stop and stay, Right over the place where Jesus lay.”

Click here to read all nine verses of The First Noel.

Click here to hear Claire Crosby and Family sing The First Noel

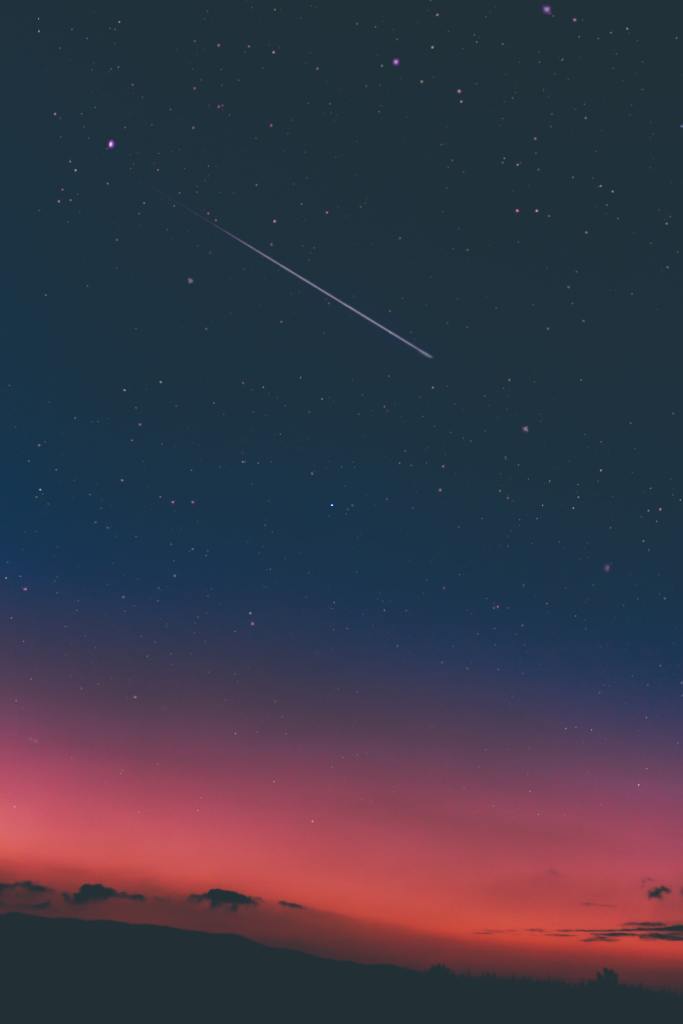

*Image courtesy of Jon Tyson and Unsplash

**For this post and others like it, see www.johnjfrady.com